Author: Tony Gaston, author and ornithologist

Long ago, ravens formed a strong presence in human culture. Throughout the Indigenous Peoples of the northwest coast, they were and still are regarded as the progenitors of creation. For millennia, their lives were intertwined with those of humanity but a few centuries ago, that bond was broken: Europeans had no use for big crows. They drove them into the wilderness.

But the ravens were patient. They waited and watched. Today, practically everyone in Canada has had some sort of encounter with ravens. From being a shy bird of forests, mountains, and tundra, they have – within the past two decades – become a familiar sight in most towns and cities. Their relationship with people is still wary. They remember the guns and traps of yesterday, but their boldness grows with every year. Ravens are intensely observant birds and among the cleverest of the winged nation. So, what do they think about us, as they survey us from their lofty perches? I often wondered that, as I watch the ravens watching me.

Common Raven. Photo: Aaron Pengelly

My travels have brought me close to ravens in the Sahara Desert, on the high plateau of Tibet, among colonies of Arctic seabirds, and, most especially, along the shores of Haida Gwaii. On the forest-clad islands of Laskeek Bay, where I studied burrow-nesting auks, ravens were a daily presence and their skill and opportunism had to be considered in our every act. They could wreck our research by locating marked burrows and killing our study birds and they could snatch away anything left lying unattended. It was we who became the wary.

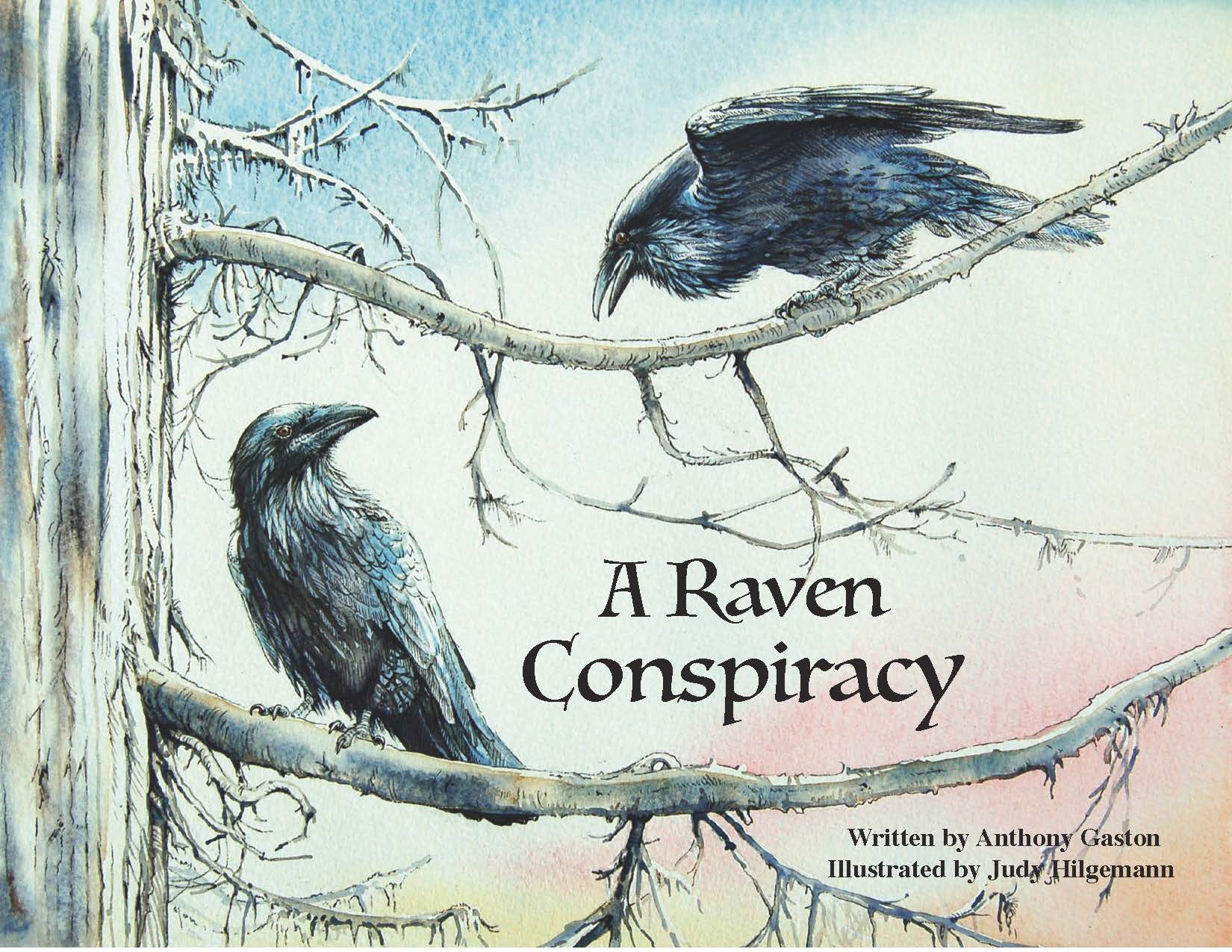

In the patience and skill of the Haida Gwaii ravens, the breadth and subtlety of their language, the use of traditional nest trees and traditional territories, I saw many parallels with traditional human societies. What if we could communicate with ravens? What could we learn? What could we teach? Together, what might we achieve? These thoughts were the genesis for my latest children’s book, A Raven Conspiracy.

Haida Gwaii, BC. Photo: David Bradley

Far back, before modern people had left Africa, ravens – as the most intelligent of birds – led the ordering of nature in the world. At first, we collaborated with them, but as we grew stronger through our tools and weapons, and especially our machines, they became unnecessary and we pushed them aside. They watched as we plundered more and more of the Earth’s resources and a feeling grew among them that the whole of nature was imperilled. A great conclave of ravens was assembled in Central Asia, attended by representatives from throughout the raven’s range. They decided that they could no longer stand aside. Their plan was not to fight, but simply to open people’s eyes to what was being lost as we tore nature apart. To attract our attention, they enlisted the help of a few children in every country, making use of the fact that the ability to speak in ravenish persists in some young children. Although the conspiracy had no immediate effect, seeds were planted that showed promise for the future.

My book aims to be both an adventure story and an environmental teaching, as well as an imagining of what the ravens who watch me may be thinking.

About the Author:

Tony Gaston, brought up in England, has spent his whole life studying birds and natural environments. He has written detailed studies of the lives of Ancient Murrelets and Thick-billed Murres and he has met and studied ravens in the coastal forests of British Columbia, the Scottish Highlands, the Central Sahara, the Canadian High Arctic and the trans-Himalayas of India. He worked in Haida Gwaii for more than 30 summers and counts the ravens who live there among his closest friends.