Swainson's Thrush

By John Neville

COVID-19 kept me at home this year in the springtime so I was able to enjoy the birds in my own backyard on Salt Spring Island, BC. On May 9 I first heard the “whit” calls of a Swainson’s Thrush, Catharus ustulatus. The next day he tried out a few songs, then went quiet until May 17. Since then his lovely, flute-like, upwardly spiraling songs have graced my yard every day!

I don’t know when the female arrived, but they have chosen a thicket across the road from my gate to sing, call, and nest. It consists of alder and cedar, with a thick tangle of blackberry and ivy. The high tide line is about 5 m down a bank. He usually sings constantly from the thicket, with traffic passing about 2 m in front of him. Our yard, and the roadway north to the letter box is a little less than a hectare. Both birds visit all around this territory, singing or calling, but no further. Another Swainson can be heard just to the south and their territories abut. To the north, the next Swainson is about 0.5 km away. If I walk down the drive (straight towards him) he stops singing and sometimes gives sharp “whit” alarm call. When I or other people walk along the road past him, he usually continues to sing. His song is easy to hear throughout his territory and acts like a vocal fence. I’ve only heard one angry exchange of calls and songs with the bird on the south side when they met at their boundary. The birds are easy to hear, but hard to see, hiding in thickets and shady places to nest, feed, and vocalize. They are quite common all across the continent in the Boreal Forest and other woodland places south into the U.S.

Pacific Russet-backed subspecies of Swainson’s Thrush, Sooke, BC. Photo: Heather Trondsen

Our bird is a subspecies of Swainson’s Thrush called the “Russet-Backed,” located in the Pacific region. Its back is a rufus colour and it has brownish spots on the throat and chest. In other parts of the continent, Swainson’s Thrushes may have a grayish-back or be olive-backed in colour.

These birds are secretive, spending most of the time in shady areas. I referenced birdsoftheworld.org to find out that they eat: beetles, caterpillars, ants, flies, grasshoppers, and a variety of berries. The female was foraging in a thicket at the back of our property on May 22 and revealed herself by her “whit” and “whit-purr” calls. She allowed me to stay only 2 m away and continued to call for several minutes. I only knew that it was the female because her partner was still singing down by the water.

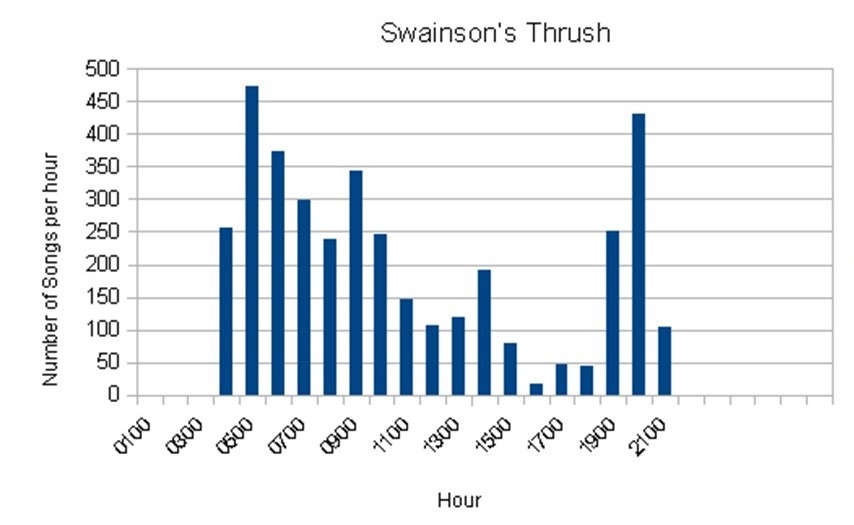

The beautiful ascending, flute-like song seemed to occur effortlessly all through the day. I recalled Louise de Kiriline Lawrence’s count of a Red-eyed Vireo’s song many years ago and wondered if I had the mental fortitude to count the Swainson’s song. So at 0400 on May 24 I sat-down outside of our kitchen door about 25 m from the waterfront thicket. Dawn was officially at 0520. However, the slightest hint of light in the sky seems to trigger birdsong. The Swainson gave two “whit” calls and began to sing at 0430. The female gave some accompanying “whit-purr” calls. He was followed 5 minutes later by a Song Sparrow and 15 minutes later by a robin. There were 255 songs in the first 30 minutes.

Dawn is the time when he is most anxious to defend his territory and in the 0500 hour, sang 473 songs. He has moved several times to the north and south but 90% of the time stayed in the thicket. He was just a little slower in the 0600 hour with 374 songs. It began to rain in the 0700. He took an 11-minute break but continued to sing while five cars and a boat passed. Very noisy young House Finches and starlings also made counting difficult but the total was still 299.

He continued to become more assured of his territory with 239 songs in the 0800 hour. His rate increased slightly in the 0900 hour with 344 songs. In the 1000 hour a very noisy coastguard hydrofoil went by causing the bird to increase his volume a little. A passing jogger made him change briefly to sharp warning “whit” call. He took a ten-minute break and still sang 246 phrases. His rhythm did not change for passing Canada Geese, Osprey, Belted Kingfisher, or a Bald Eagle imitation by a starling.

Singing frequency of a Swainson’s Thrush on May 24, 2020. Figure: John Neville

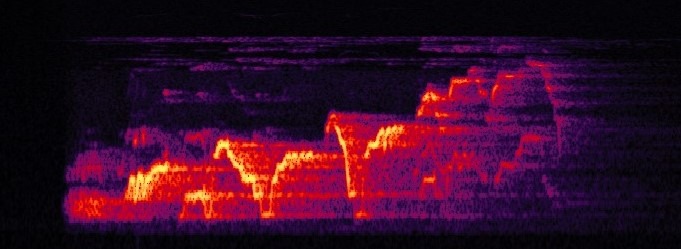

Spectrogram capture of one uprising song note of a Swainson’s Thrush.

There were only 146 songs in the 1100 hour, but there seemed to be communication between the pair. The male gave several soft “whit” calls between songs and the female responded with a more melodic “wheet” call. The male continued to sing but added several “wheet” responses between songs.

The number of songs really slowed down in the afternoon. 1200 hour -107, 1300 -120, 1400 -191, 1500 -79, 1600 -18, 1700 -47, and at 1800 only 44. I was relieved in the 1900 hour that the pace picked up again to 251. My concentration had been slipping during the slow afternoon.

The 2000 hour was even better – he sang 430 times, almost as fast as the 0500 hour! 2100 was officially twilight time. The bird sang another 104 times until 2125. During the last sequence the female added four or five “whit-purr” calls, before the pair settled down for the night in their thicket. After 3707 lovely Swainson’s Thrush songs, I was also ready for bed.

Thank you to John for sharing his story and observations with us! John Neville is a Birds Canada member and participant in the BC Coastal Waterbird Survey and BC/Yukon Nocturnal Owl Survey. He has been creating a professional quality catalogue of wildlife audio recordings since 1993. Neville Recording has produced over 15 productions featuring regional bird sounds across Canada suitable for beginners and experts alike. His most comprehensive work is Bird Songs of Canada, a four-volume collection with 396 tracks featuring 435 species. Visit Neville Recording at http://nevillerecording.com/nr_catalogue.html to find a complete list of his work.