Written by Donald MacPhail with information from David Myles, Jim Wilson, and the staff and archives of the New Brunswick Museum. David, Jim and Don are all long-time Christmas Bird Counters.

Northern Goshawk. Photo: Réjean Turgeon

It was 9 a.m. on Christmas morning 1900. That was the moment when, according to National Audubon Society data, “Wm. H. Moore of Scotch Lake, York County, New Brunswick” became Canada’s first Christmas Bird Counter.

After stepping out the door of his farmhouse that morning, Wm. H. did what Christmas Bird Counters do today. He noted the temperature, the cloud cover and the wind. And then he started to count birds. Not just the number of species, but the number of individuals of each species as well.

The figure below shows that Wm. H. was outdoors for one hour and found 36 birds from 9 species. Or did he? As can happen with any dataset, there is a discrepancy in the 1900 report. The summary indicates a total of 9 species, yet only 8 are listed. Was there a transcription error, a typo in the total, or is there a missing species? Unless Wm. H.’s original report still exists somewhere, we may never know.

Source: Bird-Lore, Vol. 3, 1901

Canada had one other participant in that first ever Christmas Bird Count. E. Fannie Jones started counting birds somewhere in Toronto at 11:30 Christmas morning, noting that the weather was clear with light winds and just below freezing. She put in a lot of effort, continuing her count until almost dark at 4:30 p.m. and identifying 41 birds from 4 species – maybe not too impressive compared to recent years when the Toronto count has yielded over 90 species, but did Wm. H. and Fannie even have rudimentary binoculars? They certainly didn’t have dozens of other people covering the area with them as many groups do today.

Neither Fannie nor Wm. H. made note of the distance covered or their mode of transport as today’s Christmas Bird Counters do. With the Model T car not coming into production for another decade, it’s pretty certain they walked.

That first Christmas of a new century was a formative time in North America. Canada was less than 35 years old and the U.S. had been through a devastating civil war which ended just two years before Canada was born. In the natural world, an idea was dawning that the human species, with its ability to change, control and wreak havoc on its own environment, had to also look after that environment.

The Christmas Bird Count was proposed as an alternative to the then-popular, and now seemingly insane, Christmas side hunt. The side hunt involved one or more teams – or “sides” – going out into the fields, woods, and waterways and blasting away at whatever living things they could find. The side with the greatest pile of feathers and fur at the end of the day was declared the winner. With activities like this, some people in both North America and Europe were starting to realize that the survival of the human species depended on the protection of other species.

Wm. H. was not out of bed early enough to be the first-ever Christmas Bird Counter. A couple of people in New England and further south started their accounts at 7:30 a.m. But he and Fannie were a rare breed as only 27 observers, representing 25 count areas, mainly around New York and New England but including count areas in Florida and California, participated in the first Christmas Bird Count. Today’s more than 70,000 Christmas Bird Count participants count birds in over 2500 Count Circles and are part of the largest and longest-running Citizen Science project in North America.

The many volunteers who coordinate Christmas Bird Counts these days find the logistics and communication daunting at times – but would it have been easier to organize in 1900? Just how did the information that there was going to be a bird count on Christmas Day 1900 get disseminated around North America including to a farmer based in rural New Brunswick, Canada?

Reporting the results could not have been easy either. Consider that Wm. H. and 26 other participants from all over North America wrote out their sightings and weather data in longhand – or maybe in a few cases used a new writing machine called a typewriter. They would have mailed their reports – using envelope and stamp type mail – to the Audubon Society in New York. And by February 1901, results, along with a number of other articles, were published in a magazine called Bird Lore and mailed to subscribers around North America. Not bad for more than a century ago.

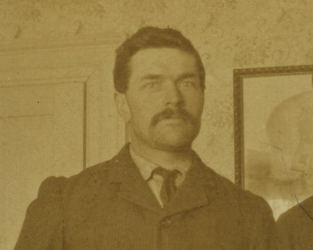

William H. Moore. Source: New Brunswick Museum.

Cropped from File X10983.

But who was Wm. H. Moore? We know that he was born in 1869 and was a farmer based near the small community of Scotch Lake, up the St. John River from Fredericton. He was not the only member of his family who got involved in the out-of-doors. He had a brother and nephews who built canoes, operated fishing camps, and worked as hunting guides. Wm. H. had a lifelong interest in birds and frequently gave talks on nature to schools and teachers. He authored “A List of New Brunswick Birds” in 1928 and kept extensive field notebooks, which are accessible in the archives of the New Brunswick Museum today.

He began teaching himself taxidermy at age 14 and around 1899 prepared the skin of one of the last wild Passenger Pigeons in North America. Over 200 of his bird specimens are still available for study at the New Brunswick Museum.

Like many naturalists of his time, Wm. H. made observations on everything in nature from moles to flowering plants to moose to the North Star. He particularly noted the different locations of the North Star during his 1929-30 travels with his daughter Nettie as they crossed Canada to British Columbia then returned home via the Panama Canal, New York City, and Saint John, New Brunswick. While in Vancouver, Wm. H. noted the presence of European Starlings (released in New York’s Central Park in about 1890) and hoped that they would not make it to Scotch Lake. Well, one of his taxidermy specimens from the 1930s is of a European Starling from Scotch Lake!

Nettie was a dedicated naturalist, too, and it is interesting to see the evolution of bird names between her and her father’s field notes. A Golden-winged Woodpecker to her father (and Jean-Jacques Audubon as well) was a Yellow-shafted Flicker to Nettie – and a Northern Flicker today. Not to oppose change, but isn’t Golden-winged Woodpecker a great name?

For unknown reasons, Wm. H. never participated in another Christmas Bird Count, but he might be interested to know that his Scotch Lake territory is within the Mactaquac Count Circle, which has been an active Christmas Bird Count area for at least the last 50 years.

Fittingly, both Wm. H. Moore, who died in 1950, and his daughter Nettie, who died in 1980, are buried within the Count Circle.